December 9th

Twenty-four Doors: Black Paint Won't Dry

Nine dusks into December, a room learns to open. It isn’t a miracle and it isn’t a trick. It’s paint. Matte black, a finish that eats the light and gives almost nothing back.

Mara and Lee just bought the place. The nursery used to be a sickroom. The realtor didn’t say it, but the neighbors did. An elderly mother in that bed by the window. Months of home care. Too many long afternoons. The kind of quiet that grows teeth.

They want the nursery black.

“It’s like a womb,” Mara tells me, palm low on her belly. “A night sky you can sleep inside.”

Lee is practical. He talks about decals, a projector, glow‑in‑the‑dark stars. He lists each plan out loud, the way some people test the bridge by stepping on every board.

I’ve painted stranger requests and worse reasons. You tell me your story and ask for a color to hold it. I tape, I sand, I cut in, I roll. That’s the job. I don’t argue with choices. I make them clean.

There’s a wool blanket folded on the dresser. A flat‑pack crib in its box. A small coil of extension cord that makes me think about heat where it shouldn’t be. The window latch sticks and then gives. Outside, winter smells like snow and road salt.

I warn them it needs to be warm for a good cure. They nod. We agree on a schedule. I write the number on the estimate and we all pretend it is the most important part.

Some rooms tell you what they were built for. This one only waits.

December One — Primer

I start in the morning with the usual ritual. Mask the baseboards. Run a hand over drywall seams to feel where the mud is thin. Wipe the walls with a damp cloth until it comes away clean. The matte is true dead black—no binder sheen, no forgiveness. It will show every tremor in my wrist if I get lazy, so I don’t.

First pass goes on smooth. I cut in careful at the ceiling and roll in a wide W, blend the lap marks, roll again. The room drinks it. The light in here is simple: one narrow window, a shy winter sun, a ceiling fixture that thinks better of it and stays dim. Perfect conditions. Warm enough. Dry enough. Nothing to complain about.

By afternoon the radiator stops clanking. I switch to a smaller roller for the tight corner. That’s when the wall decides to be something more than a wall.

At first it’s a darker dark in the paint. A patch that won’t flash off as fast as the rest. I lean closer, expecting a greasy fingerprint I missed. It changes while I’m looking. Lengthens. Thins out. Becomes a shape the way breath becomes fog.

A figure stands in the paint. Tall because the wall is tall, stretched because the roller stretched her. Arms like cords. The mouth is a rubbed‑out oval, the kind you make when there’s a sound but you don’t want the sound to be real. I blink hard. The matte should be flat, but it has depth now, a pane‑of‑glass feeling as if someone slid a picture behind it.

I tell myself it’s nothing. Light. Fatigue. The mind loves a face where there isn’t one. I take two steps back and the shape leans forward without moving at all. I can feel cold through the glove—wild, because paint should be warm to the touch when a room is this tight and the heat’s been on all day.

I reach out like an idiot. My fingers stop a hair shy of the surface. The air there is colder than the room by a clean degree. When I do touch, the paint clings. Not wet. Not sticky. Just a tack like old tape. I peel my hand free and hear the small sound of it letting go.

Something else moves. Five pale trails press down through the matte, rippling the nap in parallel. Finger‑width. Not mine. They drag from shoulder height toward the baseboard and vanish at the outlet like a hand retreating under a sheet.

I step into the hall and breathe until my heart decides to be a heart again. Then I do what men like me do. I make up reasons. Maybe I rolled too heavy. Maybe the humidity is higher at that wall because of an outside pipe. Maybe the furnace is kicking unevenly. Maybe I should eat something.

Back inside, the figure is gone. The patch is drying. The room is a room.

I wash the brushes and lay them out on the plastic, bristles combed straight. When I fold the drop cloth, I notice my roller frame. The metal is clean, but the grip bears a set of prints that don’t match the way I hold it. A little higher. A little narrower. Black on black, only visible when the light hits at a cruel angle.

I tell myself I’ll mention it tomorrow if it happens again. No need to scare anyone with a single bad minute. No need to give the room a story before it earns one.

On my way out, I test the window latch once more. Stiff, then smooth. Snow in the forecast. The hallway smells like stew and dust. The nursery behind me is quiet as a lake and about that forgiving.

I lock up, write “humidity?” on the back of my hand, and pretend that will help.

December Two — Paint

I come back with coffee and the small roller I trust for corners. The first coat has settled into a gentle flat, the kind of matte that forgives nothing and, most days, needs nothing from me but patience. I tell myself yesterday was a trick of light. I tell myself lots of things.

I start on the long wall. The roller kisses the surface and the paint lays down like velvet. Then, right under the path I just made, the black darkens further—as if the matte is a tray and I’ve just slid a photograph into developer. The picture comes up fast.

She’s standing at the foot of a bed that isn’t there. Same height as yesterday, but clearer, as if the room decided to spend more effort on the edges. A narrow woman with the posture of someone who stood too long in one spot and learned to lean on anger instead of bone. Her hands hang straight and stiff. For a long moment I think I hear breath. Not in the room—in the paint.

I pull another pass. The roller crosses her and the image changes mid‑stroke. Now she is in the bed. Home‑care neatness assembles around her: an oxygen concentrator’s blunt silhouette; an IV pole with its polite bag; a tray table parked over her lap. The bed remote dangles, its cord coiled short like someone didn’t want it reaching all the way to her hand. The TV throws a low glow that the matte eats and somehow still reflects. It looks like care if you squint. It looks like control if you don’t.

I should stop. I don’t. Stopping feels like letting the room pick the ending.

I reload the roller and make another pass, slower now. Two shapes lean into the picture from above the headboard. Their heads are too smooth, their torsos wrong, their outlines thick where the others are thin—family as shapes the mind makes when it can’t use names. One bends close with a smile that isn’t a mouth so much as a crease. The other is blocky, impatient, shoulders like a door you can’t get around. The paint goes cold where they are. My roller nap sticks hard crossing their shadows, like old tape on glass. I peel it free and the sound it makes is soft and ugly.

“Everything okay in there?” Lee calls from the kitchen.

“Good,” I answer, and my voice comes out flat. “Second coat’s taking nice.”

Mara laughs at something I don’t catch. A cupboard closes. Someone sets a pot down. Normal house noises go on like a metronome for a different song.

I work the edges, saying the trade steps in my head because they are the only prayer I know. Cut in. Roll out. Feather. Watch the lap marks. Don’t chase perfection; make the surface honest and let it be.

The scene holds. It doesn’t care about my technique. It cares that I’m watching. Details collect the way snow collects on a sill: a plastic mug with a straw that never seems to get to her mouth; a pill organizer with two days out of order; the water glass just far enough to be useless. I push the ladder an inch to the left and the picture tracks me like a portrait in a hallway.

The monsters—the shapes—bend closer. The smiling one’s outline thickens across the chest, like a person leaning weight onto a rail. The blocky one’s arms blur into single straight lines where forearms should be. I don’t need faces to know what kind of touch those are. The paint feels colder where their hands would land.

“Not today,” I tell the wall, because talking is cheaper than fear. I take a damp cloth and wipe along the baseboard to catch dust. My sleeve grazes the matte and comes away clean, but for a second my wrist tingles with that temperature of nothing.

I finish the pass and step back. The picture softens like breath on glass. The bed remains longer than the people do. So does the tray. So does the short cord.

I wash the roller in the sink until the water runs gray, then clear. I set it to dry with the others, bristles combed straight, metal shining like nothing bad ever touched it. In the hall I jot three words on the back of my hand where I’ll see them later: Reachable. Present. Within arm’s length.

I don’t tell them what I saw. I tell myself I won’t be the kind of man who spreads ghost stories in a house that’s trying to become a home. I tell myself if it was nothing, it’ll be nothing again tomorrow.

The matte behind me dries to a perfect, light‑eating black. Somewhere inside it, a woman who was asked to be quiet for too long keeps trying to talk.

December Three — Hum

Mara brings me a mug and a string of battery lights. She says she’s testing a lullaby. Not singing it yet, just the bones of it—the part your mouth can do without words. She sets the lights on the sill and thumbs the switch. Warm dots bloom along the glass. The black looks deeper for it.

She starts soft. A sway more than a melody. Three notes up, one down. I can hear the spaces she isn’t sure about. Practice is like that. You touch the shape of a thing until it lets you in.

Halfway through, she presses her palm to the side of her belly and winces. Not a big one. A blink of pain and then a breath where she waits for it to pass.

“You okay?” I ask.

“Yeah,” she says, already smoothing it over. “Just a tightness. He’s building furniture in there.” She smiles, but it has edges. She keeps humming. The next rise in the tune is thinner than the one before.

The paint answers.

It’s small at first, like a coin against a tabletop far away. A hum in the wall that has nothing to do with pipes or the radiator. The note she holds comes back to us, the same pitch, a shade lower, like someone old matching you from a different room.

Mara stops. The wall doesn’t, not for a heartbeat. Then it goes still too.

“Did you hear that?” she asks, eyebrows up, half delighted, half unsettled.

“Echo,” I lie. “This finish throws sound weird. The matte eats the high end and leaves the low. Makes it feel like it’s coming from the wall.”

She wants to believe me, so she does. She hums the line again, slower. The wall sends it back, gentler this time, as if embarrassed to be noticed.

“That’s wild,” she says, laughing, and for a second the room is only a room and she is only a mother practicing hope. The laugh turns into a cough and she touches her temple with two fingers like she’s checking for weather.

“Headache?”

“Just a flicker. I’m fine.” She sets the mug on the dresser and looks at the black like it might show her stars if she waits it out. “You’ll text if you need us?”

“I will.”

When she leaves, the light in the hall drops and the fairy bulbs on the sill become the only warm things in the world. I listen. Houses always have a pitch. This one adds a thread to it.

The hum returns. No voice now—just a tone, the one she chose, held steady at the edge of breath. The matte deepens at the foot of the wall until the bed outline is there again, faint as last night’s dream. The tray. The short cord. And at the head, the shape of a woman’s throat drawn by absence, the place where humming lives.

I don’t touch the paint. I don’t need to. The cold is already at my wrists the way lake water finds skin when you kneel too close.

“Okay,” I say to the room. “We hear you.”

The note wavers once, like a needle jumping over a scratch, and fades. The bed goes after it. The wall remembers how to be wall. The fairy lights hold.

I take the mug to the sink and rinse it like a person who has nothing on his mind. On the back of my hand, under yesterday’s words, I add one more: Listen.

December Four — Defect

The matte should be settling by now. It isn’t. A two‑hand span on the long wall keeps a shine it shouldn’t have. Not gloss—more like breath that won’t clear. I check the gauge: warm enough, dry enough. I tell the wall it can have a day to make up its mind. No sense chasing a finish that wants to argue.

Lee’s wrestling the crib box in the hall, so I offer hands. Instructions are the good kind—pictures that look like the parts you actually have. We lay everything out on the drop cloth and count hardware. He narrates each step; I let him. People calm down when the world arrives in order.

While we work, the black on the nursery wall darkens into a picture I can see without looking straight at it. A crib silhouette forms quick and neat. One slat shows a hairline split near the bottom rail—just enough to catch a fingernail. The image holds like someone pushed pause.

“Pause a second,” I say, trying to keep casual in it. I run a fingertip along the real slat twins on the floor. Third from the left, the grain lifts under my nail. A split, inside the dowel, exactly where the wall told me.

Lee doesn’t see the picture. He sees my face. “Bad?”

“Bad enough for a baby,” I say. “We don’t glue load‑bearing on a crib. We mark it and swap it. Manufacturer will send a replacement for the rail, no hassle. For today we use the spare, and we don’t overtighten.”

We mark the cracked piece with blue tape and set it aside like a thing that could lie to us if we let it back in the pile. The wall’s crib softens. The split heals in the picture and then the whole image fades into good, even black.

We finish the build slow. I read the steps out, and Mara calls stop when a bolt nips too hard. Lee checks each slat with a fingertip’s width and says good out loud. Saying it helps. It teaches the room our rules.

When we’re done, I look back at the stubborn patch of paint that wouldn’t dry. It’s flat now. No shine. No breath. Like it heard us choose the safe thing and decided to do the same.

On my palm, next to yesterday’s words, I add Replace, not fix. Then I snap a photo of the taped rail for the warranty email and leave the nursery to cure in its own time.

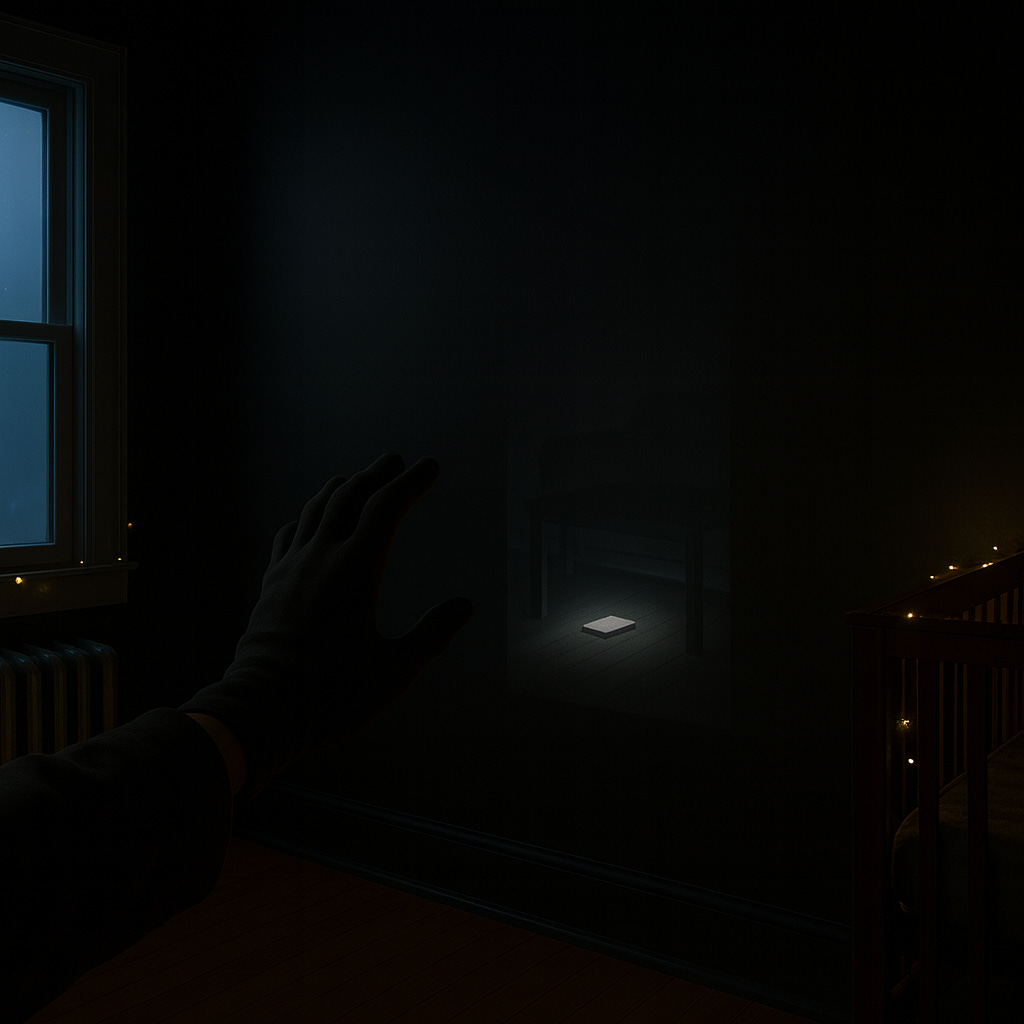

December Five — Phone Under the Table

I let the nursery sit and step into the hall to give the finish its dignity. Dusk leans into the window early. The fairy lights on the sill switch themselves on, or maybe someone touched the timer and I missed it. Either way, the black deepens. The room does its trick.

The wall builds a scene I know before it resolves. A low rectangle of light forms first, a pale square on a darker floor. Then legs of a coffee table appear above it, the underside sketched in with shadow. The little light blinks, pauses, blinks.

I don’t touch the paint. I don’t need to. I’ve been in that living room enough to know the table.

“Back in a sec,” I tell the wall, because I’ve started talking to it and stopping now would feel rude.

In the living room I kneel, reach under, and hook out a phone that has tried to vibrate itself invisible. I wipe drywall dust from the case with my sleeve and follow the sound of voices to the kitchen.

“Mara?” I hold it out. “Think this is yours.”

She glances at the screen and the warmth drains from her face, not with fear, exactly, but with focus. “It’s the clinic.” She answers. “Yes, this is Mara… yes. The tightness again, and a headache earlier… okay.” She listens, eyes on the middle distance. “We can come now. Not an emergency, understood. Today is better than tomorrow.”

Lee is already pulling his coat from the hook. “Shoes,” he says, like he’s reminding himself how to be a person who leaves the house. He looks at me once, quick. I nod like a man who was only ever here to paint.

Mara ends the call and slips the phone into her pocket like a fragile thing. “Thank you,” she says. “I didn’t even hear it go.”

“Go,” I tell them. “I’ll lock up.”

They’re gone in a shuffle of winter and worry. The house exhales the way rooms do when a plan finally has a shape.

I stand in the nursery a minute more. The square of light under the painted table fades, then goes out. The matte returns to honest black. I put my palm to the cool spot and say it out loud so the room can stop its worrying: “They got the call.”

The wall lets go. For once, that’s all it wants.

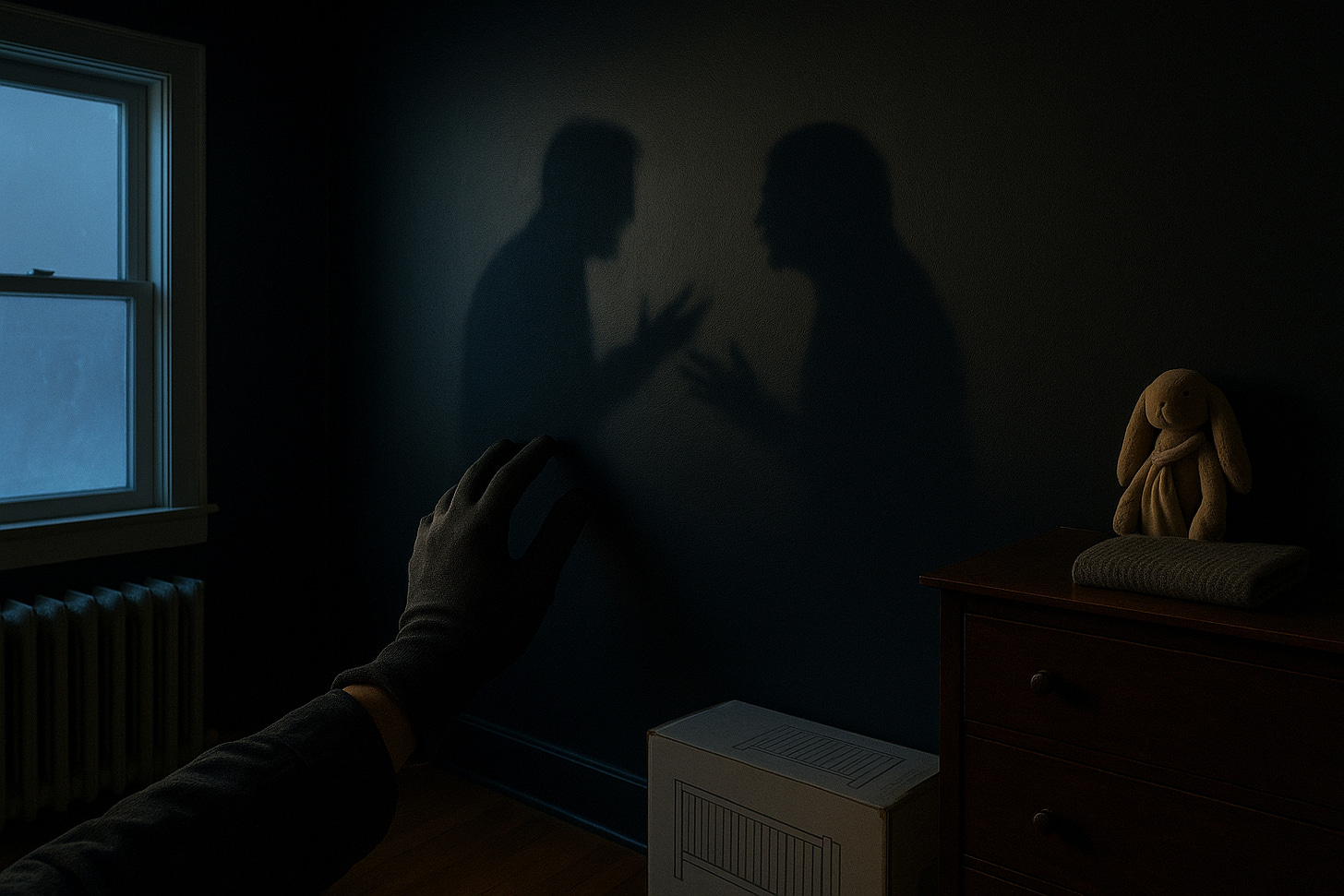

December Six — The Argument

The next day, they’re home before dark. Clinic wristbands on the counter, discharge printouts folded under a magnet. Results pending. More labs tomorrow. Nothing to panic over, nothing to ignore. We move around each other carefully. I fuss with trim; they make tea and try to build a normal evening out of small sounds.

At dusk the wall decides not to be polite.

The black deepens on the south side until two figures rise out of it. Not stick people—full bodies, shoulders and hands and the tilt of heads. There’s no sound, but mouths make shapes. I know which shape why is. I know the shape of a name when it isn’t the baby’s. Mara’s mouth opens on both.

Lee’s silhouette shrinks without moving, the way a man does when he gets caught by the one person who mattered. He looks caught and defeated at the same time. In the picture, the crib we built is there, real and wrong at once, and there’s the shadow‑weight of a baby in it that does not belong to today.

The argument plays in gestures. Mara’s hands are open, then fists, then open again—offering or demanding. Lee’s hands hover at his sides as if they used to know what to do and forgot. The scene jumps a frame and Mara reaches into the crib, gathers the small shape, and leaves the room. The walls around the picture seem to lean with her. Lee drops to his knees as if someone finally cut the string that was holding him up.

The image thins and goes. The paint looks like paint again. My chest keeps the weather.

I didn’t think they were the type for this kind of storm. But anybody can winter.

I find Lee in the hall, checking the coat hooks like they might have answers. I don’t ask permission. I tell a story.

“When I was younger I had a woman who would’ve married me. I told myself one night didn’t count and then tried to paint over what I’d done. Turns out the colors of an affair don’t match anything. I let them spread until they were the only thing you could see. I don’t have a wife. I don’t have that life because I let it happen and then lied about what color it was.”

He studies the coat rack like it’s a diagram he should’ve read earlier. His fingers find his key ring; the keys clatter once, then go still. His mouth opens, closes. “There was someone—” he starts, and stops. The keys turn in his palm, metal on metal. “Not anymore,” he says. “Not now.”

“Good,” I say, because it’s the only word that doesn’t try to decide the rest for him.

Back in the nursery, the matte holds steady. No picture. No hum. Just a wall, black and honest, waiting to see whether we mean what we just said out loud.

December Seven — Hum Goes Flat

Dusk smudges the window early. I don’t touch a brush. I sit on the drop cloth and let the room do what it’s been doing.

The bed builds itself on the wall again, crisp as a schematic. This time the neatness is a threat. The IV bag is a pale ghost, down to its last inch. The roller‑stand pump that should be clicking along sits quiet. The oxygen concentrator’s rectangle has a little green eye that ought to be on. The eye is dark.

Two shapes lean from above the headboard. I know them now—the smiling one and the blocky one. They don’t loom. They reach. One pinches the IV line and lays it over the pole just so. The other taps the power switch on the concentrator and turns it off. The outlines are calm. Practiced. The wall gives me every motion except a face.

They walk out. The room in the picture stays arranged, tidy as a staged photo. In the bed, the woman—thin as a cord and stubborn as bone—lifts her hand half an inch. Not waving. Not asking for help. Just reaching for where the call remote should have been if someone hadn’t tied it short.

Her hand sinks back. The hum we heard yesterday doesn’t come. The picture holds for one long breath and then goes flat.

It isn’t a natural death the way the wall tells it. It’s murder done with tidiness.

I stand because it feels wrong to be sitting. My voice sounds bad in the room. “What was the last owner’s name?” I ask, trying to make it small. “The mother’s.”

“Miriam,” Mara says from the doorway. She’s been watching the window, not the wall. “Miriam Rowe. Why?”

“Paperwork thing,” I lie. “Warranty on the paint. They ask about previous occupants sometimes.” I am not proud of how easily that comes out.

I step onto the porch where the air is sharper and dial the non‑emergency line. My voice on a recorded menu, then a person. “Anonymous tip,” I say. “Elder neglect that looks like more than neglect. Past tense. Address is…” I give it. “Name Miriam Rowe. Hospice equipment may have been shut off. You’ll want to look at whoever signed the home‑care logs.” The operator thanks me in a voice that has heard too much and promises a report number I won’t write down.

Back in the nursery I put my palm to the black where the bed was. The paint is cool, not clinging. Honest.

“I’m sorry,” I tell the room. “I should have asked sooner.”

The matte doesn’t answer. It doesn’t need to. For the first time since I opened a can in this house, it feels like it’s understood.

December Eight — The Fire

The walls still won’t give me a clean dry. A dull tack lingers along the long run, stubborn as a thought you don’t want. They’ve added a space heater to baby the cure. It hums in the corner, orange coil tucked behind a grate. The air tastes warm and wrong.

At dusk the paint goes from honest black to developer black. The picture comes up fast, like it’s tired of waiting for me to be smart.

Mara stands in the doorway of the nursery, the baby in her arms—a small shadow held against her chest. Lee is a shape in the jamb, one hand on the frame the way he always does. For one heartbeat they’re ordinary—posture, weight, a home counting itself lucky.

Then the wall blooms white from low and right, a flower of light that isn’t light at all, just the idea of it. The picture buckles. A table flips in the reflection. The silhouettes smear into one bright absence and then the paint swallows the scene the way a wave swallows a match.

No sound. No heat. Just the memory of an explosion the room hasn’t lived through yet.

“Lee,” I say, already crossing to the heater. I switch it off, unplug it, and carry it out to the hall. “While the paint sulks, let’s do a safety walk. On the house.”

He doesn’t ask why. Maybe the look on my face explains enough. We start at the top and work down the way you do when you’re looking for paths fire likes.

Smoke detectors first—push to test. Two sing, one chirps like a liar, one is dead. The CO detector on the main floor sits blank‑eyed. I pop the cover. No battery.

“Back in a minute,” Lee says, already heading for the junk drawer. He returns with a blister pack and we slot one in. The unit wakes, bleeps, then finds its steady green. Better. Not enough.

In the kitchen there’s a smell I don’t want to name. Not strong. Not dramatic. The kind you’d blame on the neighbor’s stove if you wanted your night back. I touch the shut‑off valve at the stove with the back of my knuckles—cool. I check the flex line. Somebody’s wrapped plumber’s tape where pipe dope should be, and on a fitting that shouldn’t have either. Amateur work.

“Got dish soap?” I ask. He does. We make a quick soapy water mix and brush it over the joints. At the midpoint, tiny pearls of air bloom and keep blooming. Bubbles where there shouldn’t be bubbles.

We don’t touch switches. We don’t pull plugs. We open the window, prop the door, and close the manual valve. Lee kills the furnace at the service switch and the water heater at the valve while I get the number for the gas company. I use my phone outside on the porch like a man who wants tomorrow.

“Possible leak,” I tell the dispatcher. “Active bubbles on a flex behind a stove. Valve closed. House ventilated. No ignition sources.” She says they’re on the way. Her voice is very awake.

Back inside, the air clears by inches. The kitchen remembers how to be a kitchen. We stand there, hands empty, like two people who almost touched something hot.

I go up to the nursery and set my palm to the long wall. The paint is only cool now. No cling. No picture. Just black doing its job.

“Not today, not tomorrow.” I tell the room. “We found it.”

Downstairs, the CO detector blinks a steady green and then, as if it wants to be included in the conversation, gives one calm beep and goes quiet again. It sounds like agreement.

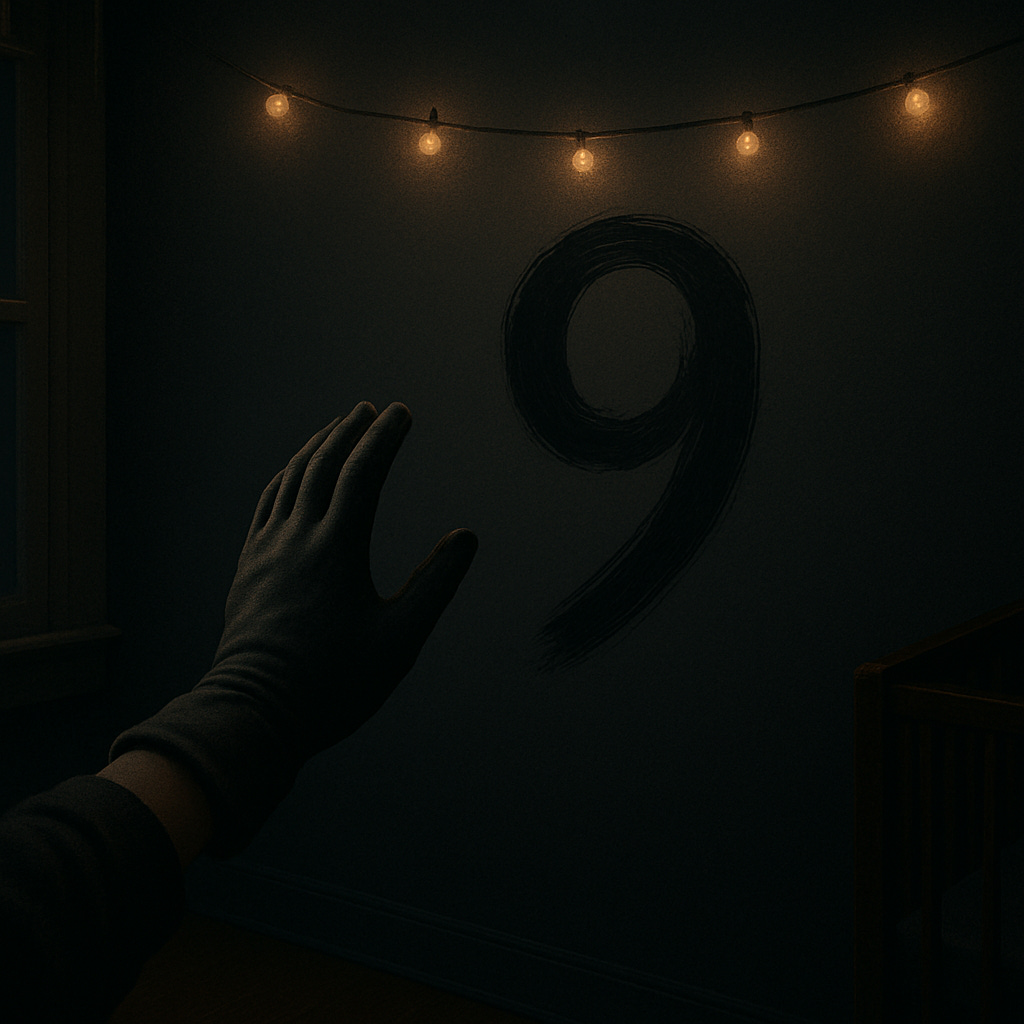

December Nine — The Touch

I’m walking Lee through why the wall still feels a little cool when Mara screams.

It isn’t a horror‑movie scream. It’s the kind you make when your body remembers something older than language and tells you to stop moving.

We run. She’s in the nursery doorway, both hands on her belly, eyes on the long wall. The shape that’s been living in the paint has stepped out of it. Not far—just a single pace—but enough. It holds together the way thick paint holds on a brush when you lift it slow. An old woman, thin and upright, made of black on black, edges trembling like wet varnish. One hand is raised, reaching for Mara and the small curve she carries.

Lee moves to go in. I catch his sleeve.

“It’s not dangerous,” I say, before he can tear free. “Don’t ask me how I know. I just know.”

He looks at me like I’m a bad idea with shoes. I don’t blame him. The room smells like fresh nothing. The fairy lights throw small moons along the baseboard. The figure’s hand stays out, waiting.

“It’s her,” I say, keeping my voice level and ordinary, like I’m talking about primer and cure times. “The old woman. Miriam. She’s been protecting the house. Protecting you.”

Mara’s breath comes short. “Protecting… how?”

“The crib,” I say. “The phone. The gas. The way she showed us every wrong thing before it could be worse.” I turn to Mara. “I think she wants to feel the baby. That’s all. If you’ll let her.”

Lee says “No,” on reflex, the way good men do when they love something they can’t replace.

“Trust me,” I tell him. I don’t make it heavy. I make it simple. “Please.”

Mara nods once—scared, but steady. She steps forward until the reaching hand is close enough to meet her. The paint doesn’t smear. It doesn’t mark her dress. The shape’s fingers settle over the curve of her belly like someone remembering the weight of a book they loved.

The room hums.

Not the broken note from before. A full tone, finished and complete, the lullaby she’s been practicing, but stronger—carried by a voice we can’t hear. The black along the woman’s arm shivers with the sound the way a window sometimes sings in the right wind.

Mara closes her eyes. “I can feel it,” she says, and the way she says it means love. “She adores him.”

The figure holds a moment longer, then steps back. The edges slacken into gloss for one breath and then flatten as the shape returns to the wall. The matte takes her in and goes still.

I lay my palm to the place where she stood. No cold. No cling. Dry. Finally dry.

Lee lets out a laugh that breaks in the middle and becomes something else. Mara wipes her eyes with the heel of her hand and looks at the room like a person who just met a neighbor she thought was a story.

“I think he’ll be okay in the dark,” I say, and I mean it. “At least in this room, he won’t be alone.”

We leave the lights gentle. We leave the walls as they are. In the mudroom I coil my cord, fold my drop cloth, and hang the roller in its stained muslin sack. On the dresser I leave a note: You can put the stars up if you want. Or not. Both are true.

The paint is dry. The room is ready. Whatever comes next can come with its hands open.

December 10th Walt Shuler

When the matte finally dried, the nursery knew it would never be empty again.

#Advent #Dblkrose #BlkSpyderPublishing #DarkFantasy #Fiction #HauntedHouse #GhostStory #TwentyFourDoors

I dig this story. Well done. 😎

This was an awesome story, and obviously you know how to paint rooms, too! Thanks for sharing it!